For decades, Highway 53 cut through the heart of northern Minnesota’s mining region, running directly over an active taconite mine and the now-closed Rouchleau Group of Mines. To ensure mining operations could continue, a 1960s agreement between the State and U.S. Steel mandated the highway’s relocation, setting the stage for a complex and vital project.

Under this agreement, the State of Minnesota was granted a surface right-of-way to use mine-owned land for Highway 53, with the mine retaining ownership of the land and mineral rights beneath the road. The agreement specified that if the minerals were needed before 1987, the mine would cover relocation costs, after which the State would assume responsibility.

In 2010, mineral rights owners RGGS Land and Minerals Co. and Cleveland-Cliffs Inc. exercised their contractual right to have the highway moved to extend mining operations. Without this relocation, the mine’s longevity – and the economic stability of the region – would have been at risk.

The State had the option to purchase the mineral rights beneath the existing highway, avoiding the need for relocation. However, this approach was financially unfeasible. The 1960 agreement required a three-year notice for road relocation, but given the scale of the project, the State successfully negotiated a seven-year timeline. Even with this extension, the project faced tight deadlines and challenges, including environmental reviews, permitting, design, and stakeholder coordination – all within Minnesota’s short construction seasons due to extreme winter weather.

Collaboration Among Key Stakeholders

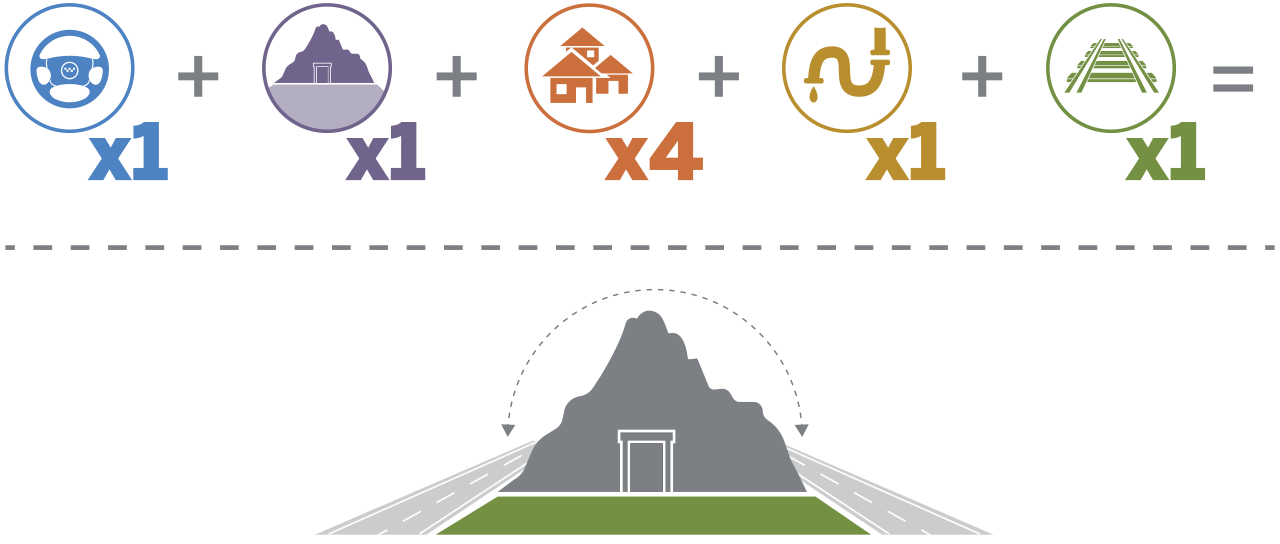

With numerous moving parts, the project required coordination among key stakeholders to ensure a successful outcome. Each played a distinct role in shaping the project’s direction and ensuring that both transportation needs and mining operations were addressed effectively. Below are the key contributors who helped make this project a reality:

Minnesota Department of Transportation

MnDOT led the effort to reroute Highway 53, serving as the State’s primary partner following the 1960 agreement with the mine owners. Their key responsibilities included managing project costs, assessing potential impacts on both the natural and human environment, and ensuring the new roadway would not be disrupted by future mining operations. MnDOT also considered the potential effects of seismic activity from mining near the relocated highway.

Mining entities

Cleveland-Cliffs Inc. and its operating company, United Taconite at the Thunderbird Mine, played an active role in the project, working closely with MnDOT and local communities. RGGS Land and Minerals Company, which owns the mine’s mineral rights, was also a key stakeholder. Together, they provided critical data on mine boundaries and mineral reserves – information essential for planning the new highway while accommodating current and future mining operations. The mine owner also had to ensure that future mining activities would not interfere with the new roadway’s location.

Four communities

The four communities surrounding the mine, established in the late 1800s and early 1900s, have long been shaped by the timber and iron ore mining industries. Mining remains a major employer in the region, making the highway relocation a matter of both access and economic stability. While each community had specific concerns about how the new route would impact local access, they also recognized the importance of working with the State and a key regional employer to support continued mining operations.

Virginia – Virginia, located directly north and east of the mine, was the most impacted by the highway relocation. Much of the new route runs through the City, requiring the relocation of water, sanitary sewer, and natural gas mains that were previously situated along the old Highway 53. Additionally, Virginia’s drinking water comes from the Mesabi Mountain Pit, the northernmost iron ore pit within the Rouchleau Group of Mines, which are now largely submerged. Any new roadway alignment near these mines had to carefully account for environmental regulations, particularly those affecting current and future water quality.

Eveleth – Highway 53 runs through Eveleth before reaching Virginia. Located just south of the mine, Eveleth sits at the starting point of the highway section that required relocation. The City’s primary concerns were maintaining access to neighboring communities and ensuring emergency services were not disrupted by the project.

Gilbert – Gilbert lies east of Highway 53, just before the highway reaches Virginia. As a smaller community, its primary concern was maintaining access to the larger cities, which provide essential services, including emergency response.

Mountain Iron – Mountain Iron is located west of Highway 53, adjacent to Virginia, where the highway passes through the mine. Some early plans considered rerouting the highway through Mountain Iron, raising concerns about how this change would impact the community.

Virginia Public Utilities Commission (PUC)

The PUC owns the water, power, and gas mains that serve Virginia, located north and east of the mine. These utility lines, which ran along the old section of Highway 53, needed to be relocated as part of the highway's redesign. The PUC played a crucial role in the planning process, as the removal and reconnection of these utilities had to align with the bridge's critical design timelines and minimize disruptions to community services.

St. Louis and Lake Counties Regional Rail Authority

The rail authority manages the Mesabi Trail, a popular public multi-use recreational trail that runs along the highway. This trail also needed to be relocated. Since the mineral rights beneath the new trail had to be purchased, it was essential to keep the trail as narrow as possible while still accommodating all of its intended uses.

Selecting the Best Realignment Route

Because buying out the mineral rights under the highway was cost prohibitive, the team began exploring a more detailed look at other alignment options for the highway, considering factors like mine operations, community access, and cost.

Options M1 and W1 were eliminated early in the process due to conflicts with mining operations, disruptions to community services, and economic impacts on Gilbert, Eveleth, and Virginia.

With those options ruled out, the project team focused on two preferred alignments: E1 and E2. Over several months, they analyzed geotechnical conditions, structural feasibility, and mineral ownership. The team presented their findings in a workshop, where stakeholders determined that Option E2 was the best choice. This decision allowed the roadway design to take a more defined direction.

With the alignment finalized, the team had just two months to develop the layout. They immediately got to work, refining roadway alignments, profiles, and geometrics. Within six weeks, the proposed layout was completed and approved by stakeholders and the State Geometrics Engineer. This approved layout then served as the foundation for the final design plans.

The team responds to the timeline

Due to the project’s tight timeline, the final roadway plans were developed alongside the environmental review process – an unusual but necessary approach to stay on schedule. Typically, environmental reviews are completed before final design begins, but MnDOT took a calculated risk, knowing that any major environmental concerns could require adjustments to the plans.

“MnDOT worked diligently with local, state, and federal agencies to ensure the environmental review stayed on track,” said Allyz Kramer, SEH biologist. “They responded quickly and professionally to questions, allowing major design decisions to move forward almost in parallel with the review.”

Kramer noted that the team’s collaborative, solution-oriented approach was key to the project’s success. Everyone involved maintained a strong work ethic, thoroughly evaluating potential issues, assessing impacts, and identifying necessary mitigations or design alternatives – all under an increasingly tight schedule.

“Hats off to MnDOT and the stakeholders for staying positive and working together, even when challenges arose,” Kramer said.

Constructing the New Highway and Bridge

With the alignment and plans set, construction began. Because the new highway still crossed mining land, the State had to purchase mineral rights – but beneath a much smaller section than the original route. To reduce costs, the road and bridge were designed to be as narrow as possible while maintaining safety and functionality.

A key engineering challenge was crossing the Mesabi Mountain Pit, a former iron ore mine and Virginia’s primary drinking water source. The team implemented stormwater management techniques to prevent roadway runoff from contaminating the water supply. One of those was the construction of a stormwater retention pond near the Mesabi Mountain Pit. This pond was designed to capture and temporarily hold runoff, allowing sediment and potential contaminants to settle before water was slowly released into the environment. By controlling the flow and filtration of runoff, the retention pond helped protect Virginia’s drinking water source while also managing excess stormwater during heavy rain events.

In the end, more than two miles of roadway was constructed on either side of a 200-foot-tall bridge over the Rouchleau Group of Mines. The bridge is one of the tallest in the state of Minnesota.

A Successful Collaboration

Thanks to a strong partnership between MnDOT, mining interests, local governments, and public agencies, Highway 53 was successfully rerouted within the required timeline.

“It was the teamwork between all of the stakeholders that really made this project come together,” said Kramer. “Without cooperation and communication between everyone involved, it wouldn’t have been possible.”

With the new highway in place, Cleveland-Cliffs Inc. has since received approvals to extend its mining operations, supporting the Iron Range communities and Minnesota’s economy. This project stands as a testament to effective collaboration, strategic planning, and the importance of balancing industrial growth with public infrastructure needs.

About the Expert

Allyz Kramer is an SEH biologist dedicated to environmental solutions with transparent processes that balance the needs of the human and natural environment.

.png?width=113&name=SEH_Logo_RGB%20(1).png)