Traffic studies and transportation plans may have gotten easier. A digital traffic engineering and planning solution offers a new approach.

This method of obtaining traffic data promises a large amount of data quickly. By aggregating location data from our mobile devices and vehicle GPS, we can now make informed traffic analysis and transportation planning decisions in the blink of an eye.

Traditional methods

According to Graham Johnson, senior traffic engineer, traditional data field collection involves spending time in the field or in front of a computer terminal manually recording vehicle license plates for an origin-destination (OD) study, with video or pen and paper. After, information is entered into a database or spreadsheet and sorted.

Road tube sensors are a traditional manual method of gathering traffic data. Data is typically gathered over a set number of days and then analyzed.

Another OD study method is sending out surveys, through the mail or online, asking drivers about their driving habits, direction, routes, etc. Setting up a series of cameras at an intersection or along a roadway is another method—the footage is then logged and studied before observations can be made about an area. A ‘truck trace’ is another, older method of capturing commercial traffic data. According to Johnson, during a truck trace, traffic engineers follow a truck on its route through an area, recording data on its movement. Other manual methods of logging roadway traffic data include laying down road tube sensors that record data when driven over—you’ve likely seen the black tubing stretched across roadways.

“Each method has its own approach,” Johnson says. “Every traffic analysis situation requires something different.”

One method of manually collecting license plate data is by recording vehicles with a video camera, then analyzing the footage.

These processes take time to complete. The number of people who respond to mailed or online surveys are seldom enough to make informed decisions. While road sensor data is good, the sensors are not typically placed everywhere throughout a city or along a corridor. What’s more, studies like these are usually only done over one or two days’ time.

Digital solutions are changing traffic data collection

Now, we can better understand traffic patterns in minutes through digital analytics platforms that offer a variety of services. The platforms offering these traffic solutions gather data by accessing location and speed information shared by cell phone apps and in-vehicle navigation systems. These are the kinds of apps that ask for permission to access your phone’s location information. The service providers then share the information with the digital analytics platforms. To help quell privacy concerns, all personally identifying information about the cell phone user is anonymized before being shared with the platforms.

Cell phone data in particular is ubiquitous and very accurate. It seems that today, nearly every person has a cell phone on them. These digital analytics platforms combine the obtained cell phone data with traditional traffic data counts via algorithm—resulting in hyper-localized, accurate information. With access to 365 days of traffic data from millions of vehicles across four million miles of U.S. roadways, traffic planning options are nearly endless.

“We now have access to a year’s worth of travel patterns and traffic data to better help us make decisions,” Johnson says. “Whereas before the data collected would typically be for only a couple of days or even just a couple of hours.”

What can you do with the data?

To use the technology, users set up a variety of queries to answer traffic-related questions. There are answers to traditional traffic engineering questions including: traveler origin and destination patterns, destinations of drivers using a certain off ramp over a period of time and what roads are most used in a specific area. The platforms can also figure out the percentage of travelers along a specified route that are going from one place to another. Traffic engineers can also use the data provided by the platforms to suggest better informed detours to move traffic onto during road construction projects.

“One of the biggest areas we’ve used these programs for is OD studies,” Johnson says. “It helps clients save money on those types of projects.”

One reason OD work well using cell phone data Johnson says, is because you can log many more trips over a longer period of time than through manual means.

With a simple OD setup using cell phone data, an intersection turning movement count can be easily estimated based on vehicle turning percentages and existing Average Annual Daily Traffic (AADT) data. This information can be used in a quick traffic analysis situation where it isn’t feasible to do a manual count due to time or financial constraints.

The platforms are continually working on new ways to utilize the data. They’ve developed algorithms that can estimate, to a high degree, AADT data on almost any roadway, without having to set road tubes.

Cell phone data origin-destination study at work

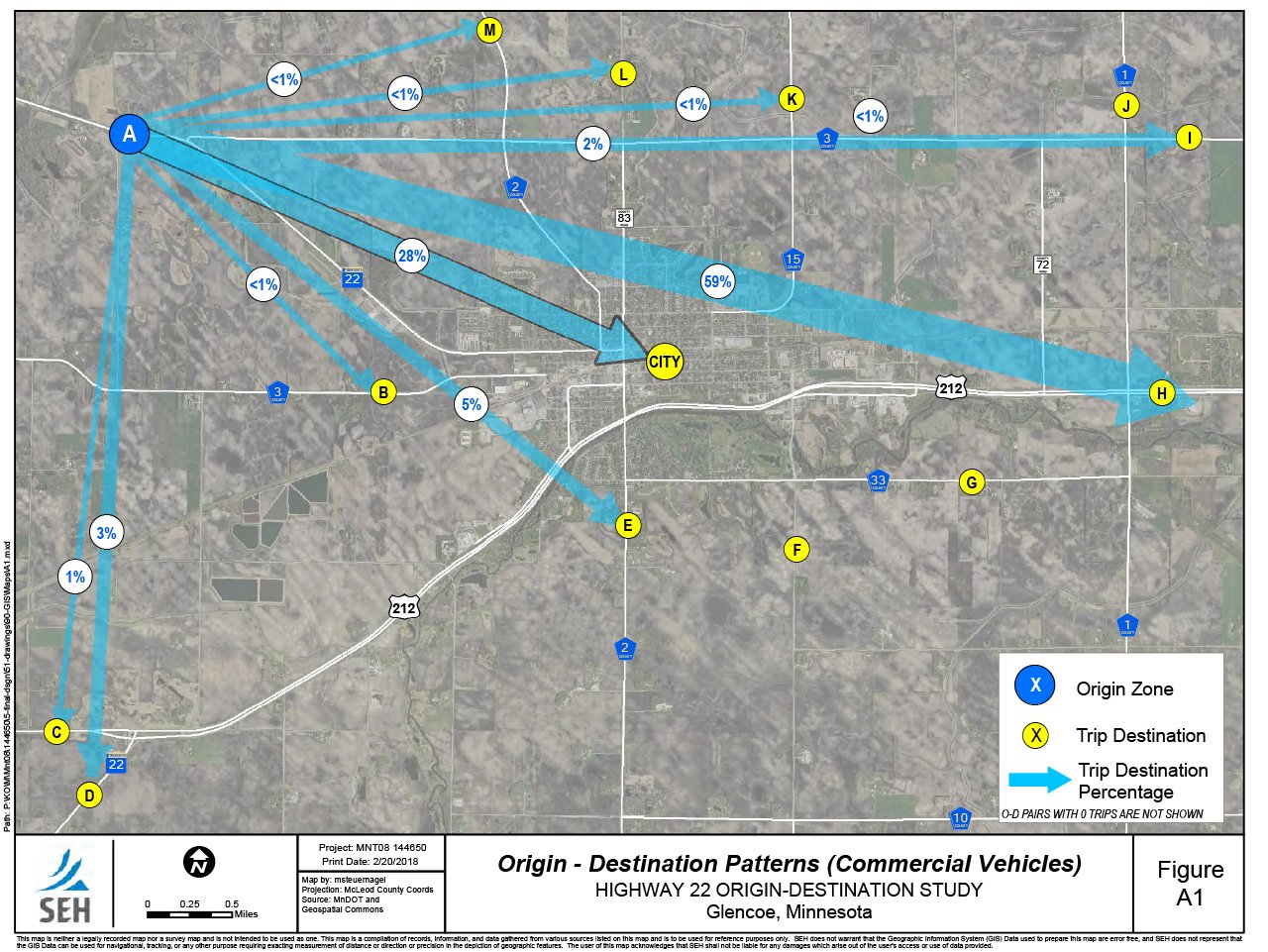

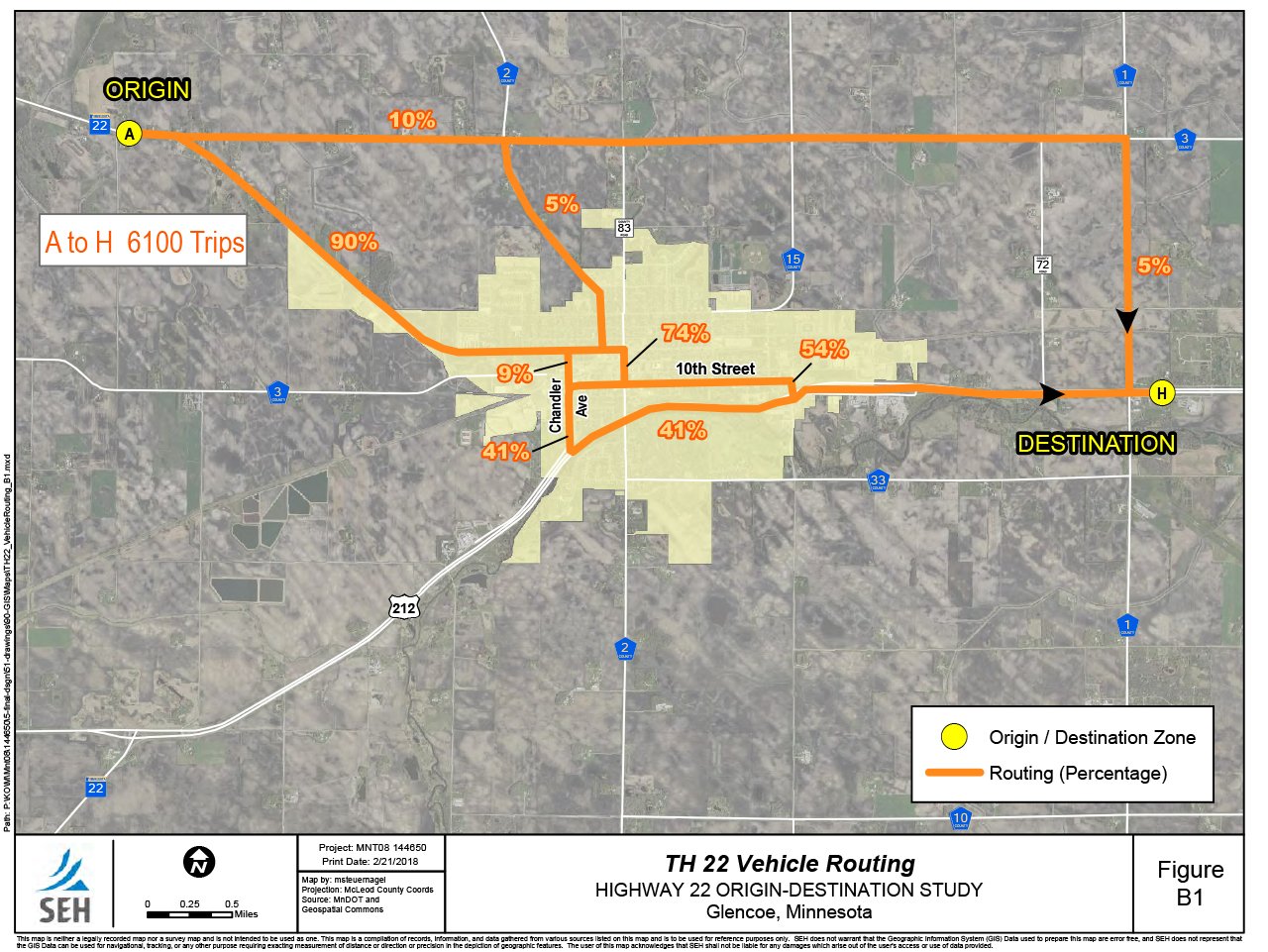

The Minnesota Department of Transportation (MnDOT) wanted to better understand the travel patterns of drivers in and around the City of Glencoe, as well as on the adjacent Highway 22. The highway enters the City from the northwest, takes a circuitous jog, and exits the City on the southwest side. Officials wanted to better understand the routes travelers were taking through the City as well as the percentage of drivers that continued on through the City to the east and those that stayed on the official Highway 22 route. So MnDOT and SEH conducted an origin-destination study using the “big data” from cell phones to track driver behavior through the area. This study had a huge cost savings compared to a manual license plate OD study.

MnDOT and the City of Glencoe, Minnesota, wanted to better understand driving patterns along Highway 22 and through the City so they conducted an origin-destination study using cell phone and GPS data.

During the planning stages of the study, the City and MnDOT wanted to know the percentage of vehicles driving along Highway 22 that actually stayed on the roadway as it entered and exited the City to the south. At that time, the most viable data source was from commercial vehicles and was the only source used. However, since the completion of the study the platforms have greatly increased the viability of routing cell phone based data.

“What we found out is that the majority of commercial vehicles driving on Highway 22 traveled through the City of Glencoe, onto Highway 212 and out of the City,” Johnson explains. “Very few, about four percent, actually stayed on Highway 22 after it circled through the City, exiting to the southwest.”

An origin-destination study in the City of Glencoe, Minnesota, used commercial GPS data to determine the majority of drivers going through the City continued their trip eastbound on Highway 212.

Data from commercial GPS in the City of Glencoe, Minnesota, indicate which streets drivers most frequent as they travel into the City on Highway 22, continuing through onto Highway 212.

Armed with this knowledge, the City is incorporating the data into their overall transportation plan study, designed to better lay out their roadways for future travel accommodations as well as current road construction projects that were in the works.

“At the beginning of the process, some thought a western bypass may help alleviate traffic through the city,” Johnson says. “But what we found out is that very few people were actually traveling that way.”

According to Johnson, tracking multimodal traffic will be much easier and more plausible using the software platforms, specifically when conducting origin-destination studies.

“If you wanted to do a multimodal origin-destination study manually,” Johnson says, “you would literally have to follow people home.”

Public engagement

When roadways are closed for repair, detours are set up. Often, these detours route traffic through residential roads or along thoroughfares that don’t typically see as much traffic. As a result, residents along these routes can become concerned—and for good reason. Increased traffic can sometimes result in decreased safety, a faster deterioration of the road and general quality of life concerns.

But, cities can use these platforms in public outreach efforts to help allay the concerns of its citizens. Traffic engineers can use information gleaned from these digital platforms to estimate traffic patterns for a more accurate depiction of how much traffic is expected along a projected detour route. This can help alleviate people’s concerns, or at least, help them to understand exactly what to expect during construction projects/detours. In cases where detours have already been set up, the public can see changes in vehicle patterns during a given time span, and how many drovers are using different routes through a designated area.

Cell phone data can be used to affirm or change decisions on the direction of traffic detour routes.

Quick tip! Public outreach

Public outreach methods can use this traffic data to target drivers along specific routes. To do this, a home-work analysis can be set up for a certain roadway and matched to ZIP code areas. The platforms estimate home or work locations based on time spent in a similar location during the day and night hours. After identifying the ZIP code with the largest number of people using that roadway, people in that ZIP code can be targeted using social media channels like Facebook. Informing people of a public meeting or asking people to fill out a survey are typical outreach target examples.

Land development

Developers can get information about the number of travelers who come to a specific area and from where they are traveling based on the home-work analysis. This information could be useful in situations where retail businesses propose building a store in a community. If a developer finds out many people regularly travel outside of their town to shop at a particular store, they may consider opening another store at that location. Or, this information can be used by competitors. If many people drive across town to shop at a certain store, then it may make sense to open a competing store nearby or along the way. Think of when you see similar, but competing stores across from one another.

Event planning

Logistics for large-scale events can also benefit from location based cell phone data, particularly events held year after year. Knowing how many people come to an event from different locations can help organizers better understand where to set up parking lots, shuttle services, valet entrances and other logistical elements. For multi-day events, the data can help identify the most popular days of the event, the number of people who drove to the event and stayed several days, how many drove in each day and left, and a host of other information that can help future planning efforts.

Limitations

As with any technology, cell phone data has its drawbacks when used for traffic engineering. In order for it to work, there has to be a cell phone connection. And, it can only track users that have apps installed with location tracking set up. Perhaps even more obvious is the fact that the driver has to physically have a cell phone on them. Because of these limits, the data from these platforms can only be considered a sampling.

“Drivers must have a phone with them. The phone has to be turned on, it has to be getting a signal and pinging off towers or that driver isn’t being counted,” Johnson says.

Vehicle GPS location data is more accurate than cell phone data. Data from commercial vehicles is widely used because most are equipped with GPS devices. Personal vehicle GPS data is available, but typically results in low trip numbers on the platforms. This data should become more widely available as the personal vehicle fleet turns over and more vehicles are equipped with GPS.

Still a place for the old ways

Despite obvious advantages using driver cell phone data, there is still a place for tried-and-true manual traffic data collection methods. According to Johnson, a manual traffic count at an intersection or on a section of roadway will be more accurate than using cell phone data—as you’re accounting for up to 100 percent of the vehicles passing through that particular area, and not just a sampling.

To the future

Ask any traffic engineer about the future of traffic and you’re likely to hear something about driverless or autonomous vehicles. So where does cell phone and GPS data come in? Johnson says it may not be the cell phones themselves but the way in which everything is transmitting data that will come into play in the future of our roadways.

“Cell phones communicate data with the world at large faster and more efficient than ever before,” he says. “With the always on connections of GPS, Wi-Fi and internet access, we’re transferring data faster now than ever before.”

Today, we have the ability to monitor traffic congestion in real time. We can also monitor travel times, parking availability and even road conditions through a variety of technology. As all of these sensors become more powerful and pervasive, engineers and planners can make more adjustments to roadway operations on the fly and offer up-to-the-second condition information to offer a safer driving experience

The information that we get from cell phone data today is just the beginning. Where we go from here is really only limited by our imaginations.

Graham Johnson, PE

Bringing it all together

With advancements in cell phone and vehicle GPS data collection, engineers and planners can quickly and efficiently collect traffic data in a fraction of the time of traditional manual methods and across much longer time spans.

About the Expert

Graham Johnson, PE*, PTOE is a senior traffic engineer focused on the future of mobility while recognizing the importance of tried-and-true methods that help people get from one place to another.

*Registered Professional Engineer in MN, SD

.png?width=113&name=SEH_Logo_RGB%20(1).png)