The U.S. airline industry has undergone significant consolidation since 2000, reducing the number of relevant players and reshaping the commercial landscape. While it seemed like this process had set the stage for an extended period of economic stability, recent dynamics more reminiscent of 25 years ago are reshaping air service development opportunities.

The impact of airline consolidation

In September 2017, the (then) CEO of American Airlines boldly stated, “I don’t think we should ever lose money again” and that American should earn $3 billion “even in a bad year.”

While this statement raised a few eyebrows at the time, it fit with the mood of the day. American generated operating income of approximately $18 billion between 2015 to 2017 while reaping the benefits of 15+ years of industry consolidation. But American wasn't the only airline with significant increases, as other major carriers generated similar results. While profitability had begun to moderate through 2016 and 2017, the obvious point was that US airline consolidation had partially immunized American from the industry’s traditional boom-bust profitability cycles.

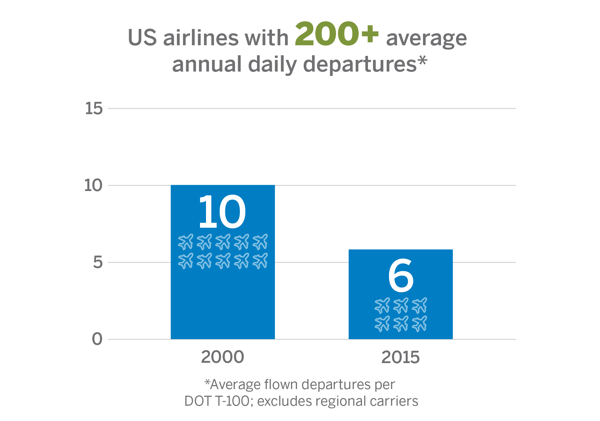

Between 2000 and 2015, the number of US airlines (excluding regionals) operating 200 or more scheduled daily departures shrank from 10 to 6. Major airline consolidations included:

- 2001: American Airlines / Trans World Airlines

- 2005: US Airways / America West

- 2008: Delta Airlines / Northwest Airlines

- 2010: United Airlines / Continental Airlines

- 2010: Southwest Airlines / AirTran Airways

- 2013: American Airlines / US Airways

Despite each combination above (and others) generally preserving existing employee groups, hubs, and other capacity drivers, domestic US airline seats decreased by 8% between 2000 and 2015, even as GDP grew by more than 30%. During this time, domestic load factors rose significantly from 71% to 85%. Although base airfares increased at a pace below inflation, the introduction of “unbundled” product offerings created significant new revenue streams through ancillary fees. Furthermore, oil prices during the 2015 to 2017 period were generally favorable.

While this period was marked by an overall optimistic industry outlook, air service development presented unique challenges. With airline margins at record highs, communities needed to offer more than a “profitable opportunity” to capture the attention of airline planning personnel, as even routes with modest fundamentals were often delivering strong margins. Pilot shortages further constrained airlines’ ability to pursue additional growth. In some cases, new service proposals backed by third-party support funds faced rejection. These dynamics brought challenges for many airports and communities, even amidst the industry’s historic prosperity.

And then came 2020. No one in the industry could have predicted the events of the pandemic era. We’re now four-plus years past the onset of the pandemic, and while unique recovery trends temporarily distorted various elements of passenger demand, more people are paying more money to fly on US domestic flights than ever before. In addition, the general US economy has avoided a severe macroeconomic downturn.

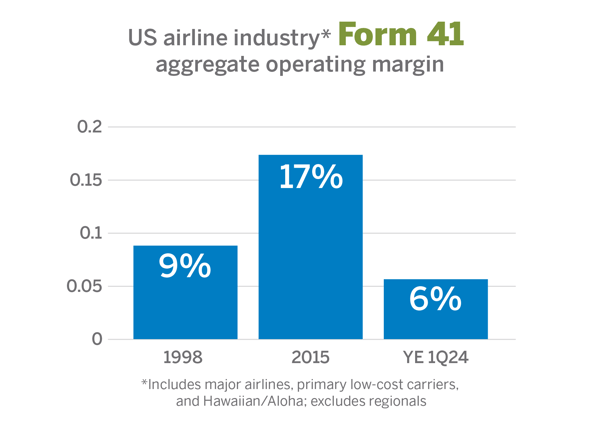

So why do US airline earnings look more like 1998 than 2015? And is this a temporary or long-term phenomenon?

Changing airline industry fundamentals

Several dynamic factors have shaped the industry in recent years. Prior to the pandemic, budget airlines were top performers. Today, however, air travelers are showing a growing preference for premium product offerings. This evolution has coincided with budget carriers strategically expanding their capacity. Recovery-era “revenge” trips created a mix of domestic and international travel over two to three summers, ultimately settling into a more stable pattern. Meanwhile, corporate traffic recovery continues to progress, with some industries and regions adjusting at their own pace.

But these feel more like short-term drivers than structural longer-term changes. So, what events have impacted long-term fundamentals?

Over the past 18 months, each of the four largest US airlines have signed new collective bargaining agreements. Based on press releases and media reports, the approximate impact of pilot deals alone is as follows:

- Delta (2023): Impact of $7 billion over four years

- American (2023): Impact of $9-$10 billion over four years

- United (2023): Impact of $10 billion over four years

- Southwest (2024): Impact of $12 billion over five years

Evaluating these figures suggests that operating margins could be influenced by over five percentage points across the four airlines combined. While a precise calculation of the margin benefits stemming from 15+ years of industry consolidation is outside the scope of this discussion, it’s worth noting that five points could represent a significant portion of these consolidation-related gains. This estimate only reflects the impact of the pilot contracts mentioned, with additional labor agreements on the horizon.

Importantly, this analysis does not prioritize any stakeholder group in terms of deserving consolidation benefits. Instead, these agreements illustrate a balanced sharing of these gains between ownership and labor. Each agreement was successfully negotiated through collective bargaining without any disruption to service.

The resulting impact on air service development

What is the impact on air service development? What’s old is new again. While higher airline expenses will increase the hurdle for new routes to project as economically viable, legitimately profitable opportunities can gain more leverage – especially those with strong support initiatives. Budget airlines, specifically, are looking for creative places to schedule aircraft as their business models evolve. The newer budget airlines are particularly receptive to creative opportunities, especially if they involve some level of risk mitigation.

Few truly structural events over the past three decades have transcended general US airline industry cycles. The 15–20-year wave of industry consolidation remains one of those events, albeit now with shared benefits between key stakeholders. This likely marks a general return to business as usual for air service development personnel with appealing new service opportunities.

What's a leader to do? Seize new opportunities! Evaluate how you can leverage strong support initiatives to attract and sustain new air service opportunities in this ever-evolving landscape.

About the Expert

Chris Warren is an air service development consultant who brings more than 25 years of commercial aviation experience, with roughly half coming from direct airline roles including the post-MBA management program at American. Over the past decade-plus, he has managed air service development programs for more than a dozen US clients across the range of market sizes.

.png?width=113&name=SEH_Logo_RGB%20(1).png)