Exploring the Realities of Design-Build in the AEC Sphere

Design-build project delivery is rooted in centuries-old practices but has emerged as a game-changer in the modern architecture, engineering, and construction (AEC) industry. By integrating design and construction services under one contract, it offers a streamlined, collaborative approach that addresses the complexities of today’s projects. Despite its proven benefits and growing popularity, several misconceptions still surround this innovative method. Here, we debunk some of the most common ones and shed light on the true potential of design-build.

Misconception 1: Design-Build is Always Led by a Developer or Construction Company

Leadership in design-build projects depends on the project's priorities and requirements. While it's true that developers and construction companies often lead design-build projects, other entities, including engineers and architects, can take the leads. For example, engineer-led design-build is common for technically complex projects such as manufacturing and industrial plants, data centers, healthcare facilities, water treatment plants, and fire stations. Ultimately, the choice of project lead needs to be dictated by the project's specific demands and goals, not by a one-size-fits-all approach.

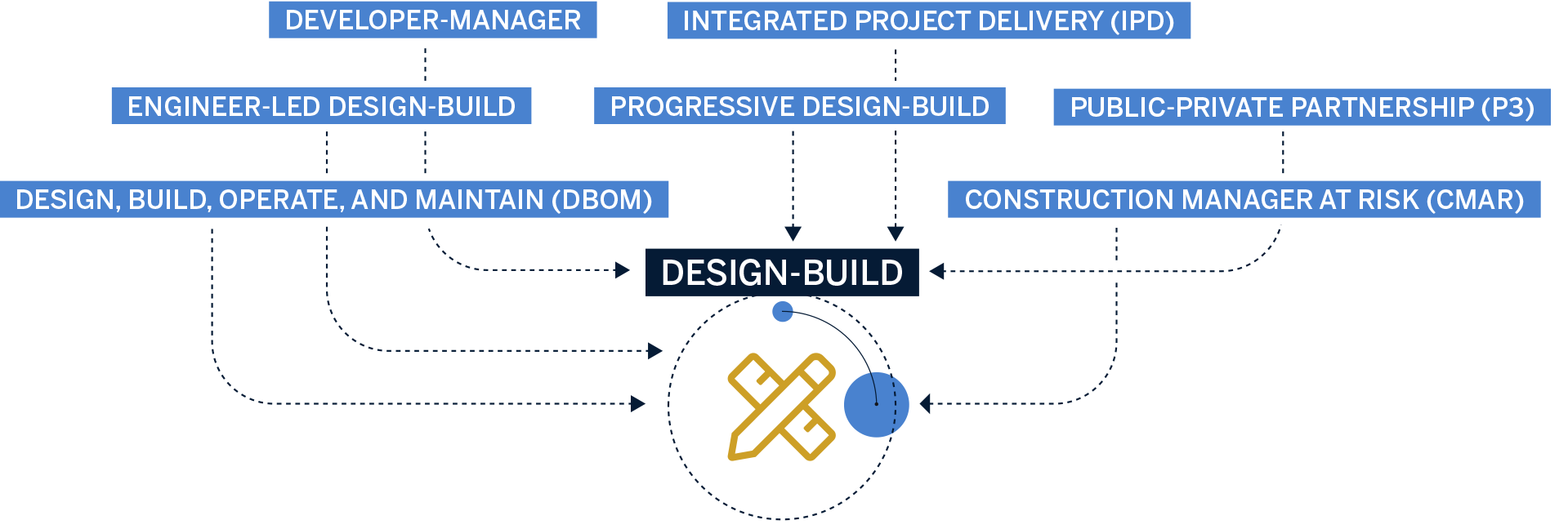

Misconception 2: Design-Build is a Single Method

Contrary to popular belief, design-build is not a monolithic approach. Over the years, "design-build" has become a catch-all term for various alternative project delivery methods. These include:

- Developer-manager: In this approach, a developer takes the lead on the project, coordinating between design and construction teams to ensure seamless execution. This method is often used in large commercial developments where the developer has a vested interest in the timely and cost-efficient completion of the project.

- Engineer-led design-build: Here, an engineering firm leads the project, making it particularly suitable for technically complex projects like industrial plants or infrastructure works. The engineer ensures technical standards are met while integrating design and construction to streamline processes.

- Progressive Design-Build: This method starts with a preliminary design and then progressively refines it as more information becomes available. It allows for continuous collaboration and adjustments, making it ideal for projects where the scope is not entirely defined from the start.

- Design, Build, Operate, and Maintain (DBOM): This comprehensive method includes post-construction responsibilities, ensuring that the project is not only completed but also efficiently operated and maintained. It's often used in public infrastructure projects like water treatment plants.

- Construction Manager at Risk (CMAR): CMAR is not a design-build method, it is a distinct delivery method that keeps design and construction separate. Here, the construction manager commits to delivering the project within a guaranteed maximum price. This method shares the risk between the owner and the contractor, ensuring cost control and efficient project delivery.

- Public-Private Partnership (P3): P3s involve collaboration between government entities and private companies to finance, build, and operate projects. While not inherently a design-build delivery method, this model leverages private sector efficiencies while delivering public infrastructure, such as highways or public buildings, making them ideal for financing and risk-sharing

- Integrated Project Delivery (IPD): IPD, while not a design-build variation, fosters a collaborative approach where all stakeholders, including the owner, designers, and builders, work together from the project's inception to its completion with different contractual arrangements. This method aims to optimize results, increase value, and reduce waste.

Each method has its own unique applications and contracting formats, tailored to meet different project needs.

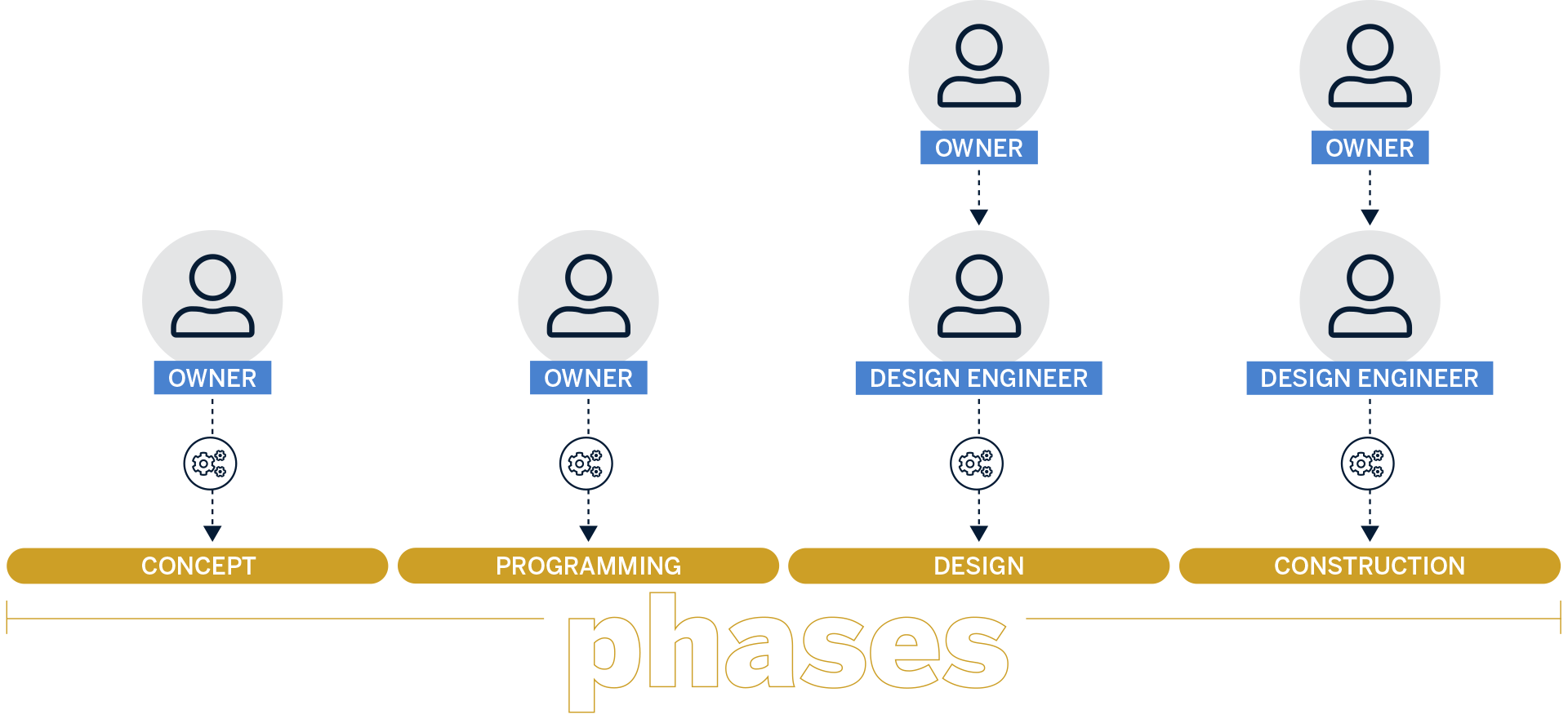

Misconception 3: The Owner Loses All Control in a Design-Build Project

Owners retain significant control in design-build projects, often more than they might expect. The level of owner involvement can vary based on the delivery arrangement. In an engineer-led design-build project, for instance, the owner engages from the onset, contributing during the concept and programming phases. The design engineer ensures the owner's input and original intent are carried through the design and construction phases. Many design-build arrangements operate on an "open book" basis, with regular progress updates, collaborative reviews, and checkpoints that encourage owners to provide input and remain engaged from design to completion.

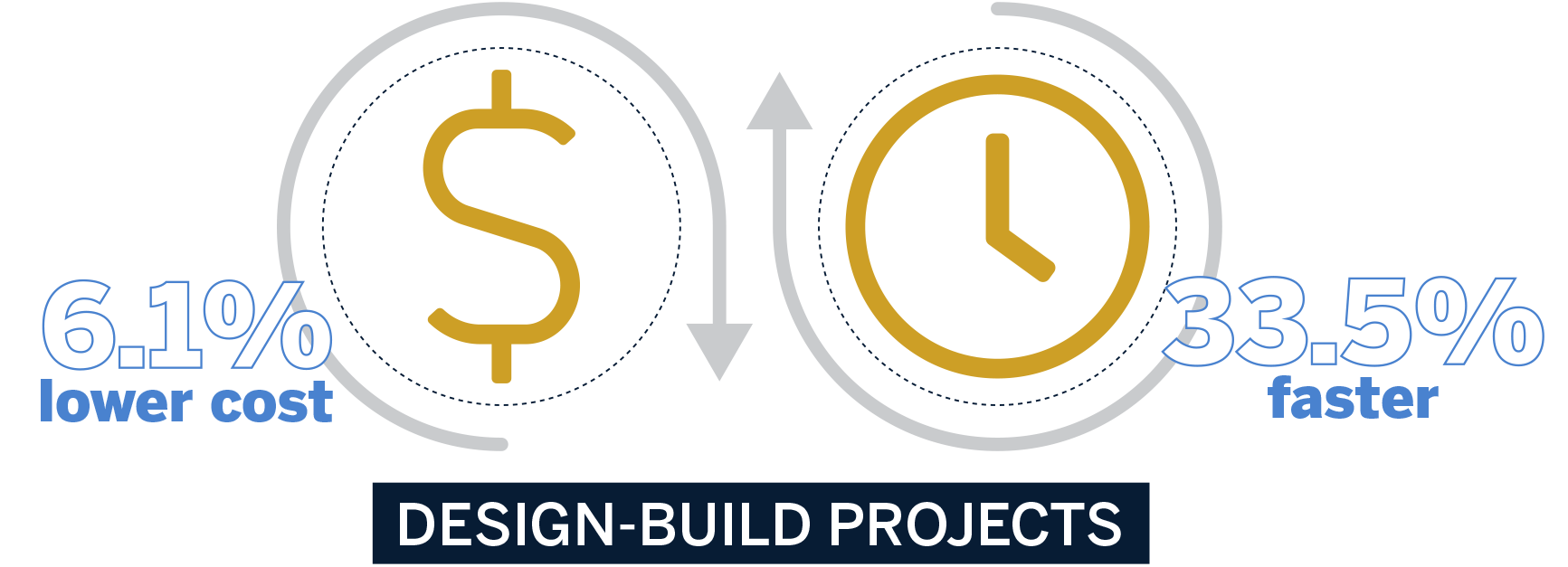

Misconception 4: Design-Build is More Expensive Than Traditional Design-Bid-Build

In reality, design-build can be more cost-efficient than traditional project delivery, but outcomes depend on project execution. According to the Design-Build Institute of America (DBIA), design-build projects are completed 33.5% faster and have 6.1% lower cost growth compared to traditional design-bid-build projects. This efficiency stems from early identification of project budget and goals, which are maintained throughout the project by real-time collaboration between designers and builders to minimize change orders and costly disputes. Cost savings vary based on project size, scope, and adherence to best practices. Poorly managed design-build projects may fail to take advantage of these benefits, highlighting the importance of selecting the right team.

Misconception 5: Design-Build is Only Appropriate for Certain Entities

Design-build is often associated with private sector projects, but many local government projects, as well as federal and state organizations, successfully use design-build methods. It is appropriate for a wide range of entities, irrespective of their size or sector, because it provides a streamlined process that enhances collaboration, accountability, and efficiency for stakeholders.

The method’s adaptability allows it to meet diverse requirements, from small municipalities with budget constraints to large federal agencies managing complex projects. The key lies in tailoring the design-build process to align with each organization’s unique needs and priorities.

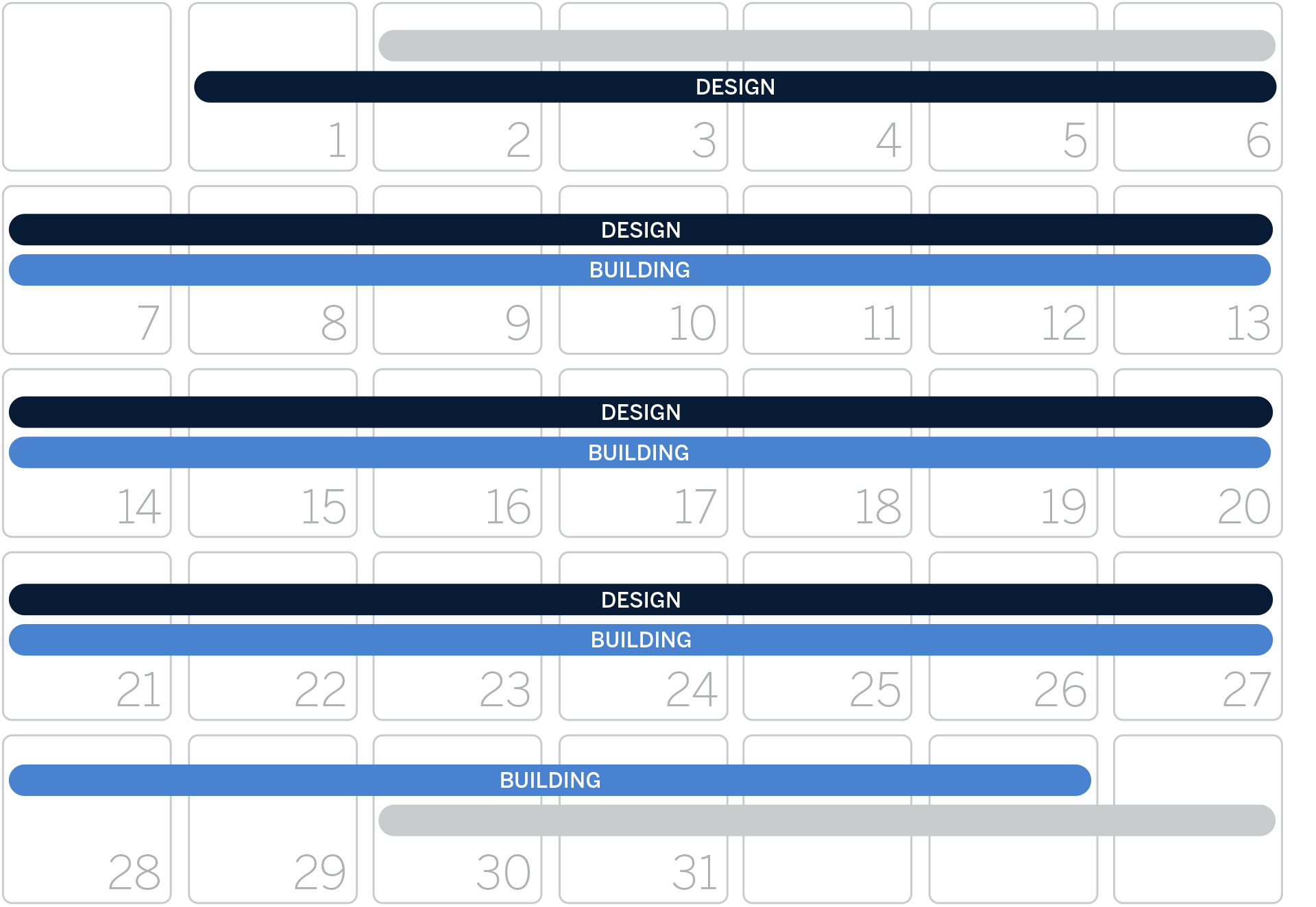

Misconception 6: Design-Build is Good for Speed, Bad for Quality

There's a misconception that the speed of design-build projects comes at the expense of quality. This is far from true. High-quality design-build projects achieve quick timelines through concurrent activities, such as building while designing with efficient sequencing, not by cutting corners. According to the DBIA, design-build projects have been shown to deliver high quality results, often receiving awards for excellence in construction and design.

The method also allows for continuous quality assurance through integrated project delivery, ensuring that the final product meets high standards. For example:

- Real-time collaboration between designers and builders helps to identify and address potential issues early in the process, reducing rework and ensuring that the project adheres to stringent quality benchmarks.

- Design-build projects are known to have fewer change orders and construction defects compared to traditional methods, leading to higher overall satisfaction among stakeholders.

Many design-build projects undergo rigorous third-party inspections and certifications to ensure compliance with industry standards, with real-time feedback ensuring that both speed and quality are priorities.

Taking it Home

The design-build project delivery method offers a flexible, efficient, and collaborative approach that can be tailored to various project needs. By debunking these misconceptions, we can better understand the strengths and advantages of design-build, paving the way for future projects collaborations.

About the Expert

Steve Peterson is president of SEH Design|Build and is a Senior Project Manager. Steve has served private, city, state, and federal clients.

.png?width=113&name=SEH_Logo_RGB%20(1).png)